The world that we live in is a world fraught with contradictions. It is also a world which is constantly structuring and restructuring itself as a result of which it necessarily modifies its various ideas and concepts. One such political concept which has undergone numerous revisions with diverse political repercussions is the idea of citizenship.

What does the word citizenship encompass? What are the prerequisites of being a ‘citizen’ of a country/state? Again, is citizenship territory-specific? If yes, how do we evaluate the status of citizenship in the context of globalization? These and many more questions accompany the idea of citizenship and tend towards diverse range of attempted resolution. Despite these discussions, we still have the Khurds and the Rohingyas attempting to make sense of what the word actually means to them.

The scope of this analysis is not to answer any of the abovementioned questions. Instead, this essay anchors itself on the grounds that citizenship is a dynamic idea which is informed and modified by various social, political and historical processes. Because the idea of citizenship is a result of various historical process, this analysis argues that understanding the origins of this idea is an imperative to understand the concept in the contemporary context and its relationship vis-a-vis democracy, legality, property, religion and political territory. Therefore, this analysis attempts to explore the idea of citizenship as it develops in the Classical period and analyze the changes it suffers by the time it reaches the Middle Ages.

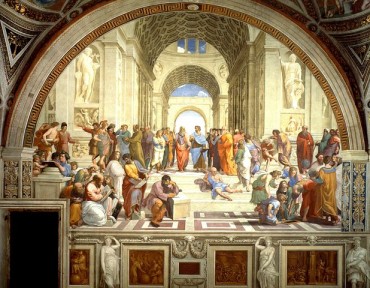

The word classical in the context of citizenship has two implications . J.G.A Pocock in The Ideal of Citizenship Since Classical Times makes it very clear that by referring to the period as ‘classical’, he is mainly referring to two of its aspects : First, to the kind of authority it has on us for having expressed an ideal. Secondly, he uses the word classical times to refer to the period when the ancient civilizations of Greece and Rome flourished and were capable of articulating the ideal of citizenship, the time period of which fall roughly between the fourth and third centuries in Athens and from third century B.C to the first A.D Rome. According to Pocock :

“ There is not merely a classical ideal of citizenship articulating what citizenship is ; citizenship in itself a classical ideal, one of the fundamental values that we claim is inherent in our civilization and is tradition.”

Pocock, The Classical Ideal of Citizenship

The Greeks had been concerned with the idea of eudaemonia or the “good life’ for a considerable period of time. While Plato refused to detach the eudaemonia from virtue, Aristotle defines eudemonia, a well lived life independently of virtue as “ The full normal functioning of a thing relative to the capacities specific to a natural kind.” Furthermore, in Nichomachaen Ethics one sees that the concept of citizenship is itself one of the attempts at attaining the good life :

“The science of the good of man is politics which deals with how to realise their good for a body of men” – Aristotle, Nichomachaen ethics.

Citizenship in ancient Athens was a prerogative of a minority of population. To be a citizen of Athens, one had to be a male, born in Athens into a known lineage. It has been often noted that the Athenian democratic civilization was based on a very large base of slaves who were denied citizenship . Also, an entire half of the population in the form of women were denied citizenship. Added to this, settlers and foreigners were denied citizenship, no matter how wealthy or economically influential they were. However, it remains a fact that democracy was practiced among the minority who had access to it. The very fact that people could and desired to come to terms with the concept of ruling and being ruled is commendable in itself. The power given to the people in order to rule is a remarkable feature of the Classical times, David Held emphasizes that :

The demos held sovereign power, that is, supreme authority, to engage legislative and judicial functions,. The Athenian concept of ‘citizenship’ entailed taking a share in these functions, participating directly in the affairs of the state.”

– Held, Models Of Democracy

The concept of citizenship in the Classical times intertwined with a firm faith in democracy. Many thinkers have often articulated this belief. Aristotle for one, does so in Politics when he propounds the ‘doctrine of the wisdom of the multitude’ :

“ Each of them by himself may not be of good quality, but then they come together it is possible that they may surpass, collectively and as a body, although not individually – the quality of the few best. “

– Aristotle, Politics

As seen above, democracy ,equality and the idea of the good life have been the driving forces behind the Athenian concept of citizenship.

Historically, the idea of democracy filtered through and took shape in various eras. Though the period where the Athenian democracy found its full bloom is considered to be 5th to 3rd century BCE , it took many years to evolve as a distinct mode of governance.. Various political forces had been at work to prepare a fertile ground for democracy to exist. Also, ideas from various thinkers have informed and modified Athenian democracy. Furthermore, when we trace the idea of citizenship from the Classical period to the Middle Ages, one can see that the concept undergoes some significant change brought about by various discourses and counter-discourses.

Historically, 500BCE to 300BCE is considered to be the period when democracy flourished in Athens. The economic reforms initiated by Solon when he was appointed the archon eponymus in 594 BCE is considered to be one of the first steps initiated towards a democratic community. His decision to cancel the debts of all the tenant farmers ( hektemoriori) and return their lands was a drastic step in reducing the great economic inequalities that existed in Attica. He is also said to have foramlised the four property classes of the Athens into pentakosiomedimnoi, the hippies, the zeugitai and the thetes. The lowest class called the thetes formed about half of the Athenian citizenry and were manual labourers. In a departure from erstwhile customs, Solon allowed all the four classes of Athenian citizenry to participate in matters related to political institutions. Such political and economic reforms have played a major role in shaping Athenian democracy which, by extension has had a major impact in determining the nature of citizenship in Classical times.

The notion that the polis and the oikos were two separate spaces was very strong and these private and public realm were supposed to remain distanced from each other. Consequently, no matters of the oikos was allowed to permeate in the realm of the polis or vice versa, great emergencies being an exception. The ekklesia was one of the most important political institutions whose access was a privilege of every citizen. The ekklesia had a quorum of 6,000 and met about 40 times a year. It is very interesting to note that there was no discrimination on the basis of economic differences insofar as one’s say in political decisions was concerned. This was in keeping with the idea that democracy, with its idea of giving political volition to each citizen, was in principle designed to benefit the poor since they are the most in numbers in any given society. Later, we see that during the Roman period, the concept of property and the existence of law withwhich to protect them carries with it the germs of material individualism and also indirectly tilts the table towards oligarchy.

Here, the one would like to focus on two very important rights (not in the constitutional sense of the term) enjoyed by the citizens of Athens which are isegoria and (more importantly) parrhesia. These terms reflect how important a concept was the idea of free speech was for the sound functioning of Athenian democracy. Isegoria stood for an equal opportunity to speak which was granted to all citizens. The concept of parrhesia on the other hand referred to the encouragement of frank and critical speech to all its citizens- something which even the largest democracies of today struggle to handle. It is parrhesia which Socrates upholds while refusing to recant before his final moments and it is also chief component of ruling and being ruled by alteration- a distinctive feature of the citizenship in the Classical times. J.G.A Pocock in The Ideal of Citizenship in Classical Times is very keen to remind us that, according to Aristotle :

“ The citizen is one who both rules and is ruled, and, that ruling becomes better in proportion in as that which is ruled is itself better, namely, endowed with some capacity of its own for the intelligent pursuit of good.” – Aristotle, Politics

Following this logic he uses the oft-repeated example of how it is better to ruler over animals than things, over slaves than animals, women than slaves, and one another above everything else.

Because power was accessible to many in a democracy, safeguarding that power from any potential corruption was an absolute necessity. Therefore a great reverence was given to the laws and a citizen was made to follow it very seriously. We see this tendency even more markedly after 546 to 526 BCE, the time when Athens was in a short spell of tyranny and witnessed the state of affairs when one is allowed to break the law.

Hence, one can also see that the zoon politicon had ingrained within him a certain regard for the law which would later come to effect when law would itself become a determining factor of citizenship and he would be transformed into legalis homo under the Romans.

About five hundred years after Aristotle , the Roman jurist Gaius was to take the course of the political universe form the real to the ideal by redefining it through jurisprudence as an entity which is divisible into “persons, actions and things.” The citizen was now seen to be interacting with each other through the mediation of things and all his actions in relation to these “things” was what was covered by the laws. According to Held :

“From being kata phusin zoon politicon, the human individual came to be by nature a proprietor of things… His actions were in first instance directed at things and at other persons through the medium of things ; in the second instance, they were the actions he took, or other took in respect of him, at law – access of authorization, appropriation, conveyance, acts of litigation, prosecution, justification…A “ citizen came to mean someone free to act by law, free to ask and expect the law’s protection, a citizen of such and such a legal community, of such and such a legal standing in that community.”

– Held,The Idea of Citizenship Since Classical Times

With the advent of jurisprudence, one can see that the concept of ‘citizenship’ in the Aristotelian sense nearly ceased to exist as neither could one ‘’rule and be ruled’ and have much say in the governance, nor was there much universality of the term which bound up all citizens, for, being a product of the law, and law being different in different municipalities, citizen came to mean different things in different places. Moreover, it wasn’t a distinct prerogative restricted to a certain group of people but a shadow of its former self given to the various subjects of the Roman Empire as it underwent expansion. The claims of Paul in being a citizen of the Roman empire can be seen as an example of this phenomenon. Terming it “the revolt of the real – and even material against the ideal and against the classical ideal of citizenship”, Held argues that it is the oikos which begins to define citizenship, for, it is the oikos where his “things” are located on which the law operates and by the virtue of which he becomes a subject to the law and hence, a citizen. Held writes :

“Possession, rather than the emancipation from possession, became the formal center of his citizenship, and the problem of freedom became increasingly, the problem of property.”

Thus, we have seen so far that by the time we reach the Gaian concept of citizenship, the political has been impinged upon by the legal (law) and economic (properties) factors. However, these three dimensions of citizenship will be hemmed in by a single force which will provide a very different version of citizenship : Christianity.

The polis during the Classical times not only provided for the material needs of the citizens but also provided an support to their moral needs. This is often seen reflected in ideas like Aristotle’s Theory of Moral Action . However, with the advent of Christianity, an apparent rift between the individual virtue and political institutions seemed to take root in public thought. What the Greeks had organized as a political community was turned into a religious community. Constantine’s conversion to Christianity in 312 CE and banning of non-Christian religions by Theodosius I in 390s allowed Christianity to establish a stronghold in the Roman Empire and by extension, in Europe. The Church, as a physical entity often served as node around which social and economic activities of the entire community revolved. Religious laws and commands of the Church had far greater moral authority than any legal system. In the political front, it discouraged political thinking by terming it to be a temporary affair of an ephemeral world.

Interestingly, after having discouraged the people form indulging in political activities, the Church itself was often in major political strife of the times, an example of which can be seen during the Reformation.

The concept of citizenship undergoes a drastic change during the Middle Ages, drenched in Christian ideology and ethos. One of the most influential figure on this topic would be Aurelius Augustine. Greatly influenced by Manicheanism, he was a firm believer in the duality between form and matter, the latter of which was considered to be intrinsically evil. Because all political and social arrangements were materialistic in nature, they were seen as being evil. Two most important books by Augustine are Confessions and The City of God. While trying to link morality with citizenship and depicting how morality is a matter of choice, Aristotle had emphasized the agency and importance of volition. Augustine , while discussing the concept of The Original Sin states that God made us creatures with free will. However, by saying that it is only through God’s grace that mistakes committed by the abuse of free will may be pardoned, Augustine places political power in the hands of an other-worldly entity and leaves no room for human agency for political action.

In the City of God, Augustine propounds the greatness of the heavenly city as compared to the earthly cities which is transitional. Preaching complete obedience to political rulers, Augustine was responsible for a large degree of political complacency which plagued the minds of the masses during the Middle Ages.

St Thomas Aquinas (1224-1274) was a strong proponent of the idea that religion had a space for logical arguments and wasn’t solely based on revelation. The Catholic Church had, for a long time, actively opposed the works of Aristotle. Aquinas lived during the time when the works of Aristotle became available for the first time in Latin and has taken up various ideas to further his views on religion and political philosophy. Rejecting that political rule is a sign of sinfulness, Aquinas argued that man is a social animal but there cannot lead a social life save under the direction of a leader. Believing that man is an animal of reason, and that reason fosters fellowship, Aquinas argues that there should be some means whereby the community may be ruled. Finally, he vouches for monarchy as the most viable option under which a community can organize itself. Interestingly, he also concedes that in some cases the rule by many may also be able to achieve what monarchy cannot. However, he also warns against the dangers of that rule of many devolving into tyranny.

In the book On the Government of Princes, he states that a people might rebel against a ruler if he becomes a tyrant. By justifying possible regicide, Aquinas goes against the Augustinian principle of absolute obedience. In keeping with the Christian spirit, Aquinas advises the ruler to carry out their rule in common interest. Aquinas’ vouching for monarchy is said to have had a great impact in furthering the same in Christian Europe. It is very evident that religion had a huge role in the political process where Classical democracy was replaced by Medieval Monarchy.

Although the concept of citizenship has changed significantly from the Middle Age to this day, the trajectory of the concept of citizenship from the Classical Period to the Middle Age is very important to understand the very nature of the term “citizenship”. This historical understanding of the term may help us better engage with its contemporary manifestation in the context of nation states and figure out the possible dimensions it might take in the future.

To cite this article , copy the following URL :

Works cited and referred :

1. J.G.A Pocock – The Ideal of Citizenship Since Classical Times.

2. St Thomas Aquinas – On the Government of Princes

3. St. Augustine – Confessions, The City of God

David Held – Models of Democracy

5. Aristotle – Politics, Nichomachean Ethics

6. Shefali Jha -Western Political Thought , from Plato to Marx

7. O.P. Gauba – Political Theory and Thought

8. Ashok Acharya – Citizenshp in a Globalizing World