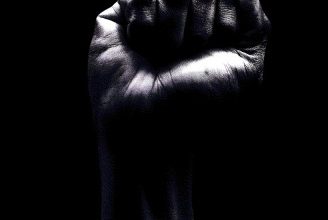

Protest songs are a vibrant part of the human heritage, arising from the very social nature of collective living wherein power equations are constantly being re-negotiated. The term “protest songs” is neither an exhaustive nor a watertight category. There may be as many protest songs as there are causes leading to protest. Protest songs have had a historical tradition which is often evoked when new songs are composed. Working on the powerful systems of references, protest songs either refer to the members of the tradition to which they belong or to the contemporary social, political and cultural references and that these references may manifest in explicit intention of the producer or be implicitly inferred by the listener.

The essay has been divided into three sections dealing with different components of the nature of protest songs. The term ‘protest songs’ in this essay refers solely to songs in the English language. Furthermore, the term ‘protest songs’ refers to the manner in which the songs of protest have been generally used and whenever used in this essay, is done so solely to fulfil the necessity of having an acceptable signifier.

Part I | The Nature and Structure of Protest Songs

With the rapid development of the American Civil Rights movement in the sixties, protest songs not only established itself as a musical genre but also as an effective political tool. A significant question one may ask here is this: What qualifies as a protest song, or to be more precise, what is it in a song which makes it a protest song? This has been the fundamental question asked by theorists who have attempted to define the category of protest songs. In the earlier stages of this process of defining, it was understood that protest songs are such because of their intent, as a result of which it was the lyrics which was subject of analysis. Serge Denisoff goes so far as to categorize protest songs in neat boxes of “persuasion” and “propaganda”, tracing protest songs to the revivalist Protestant tradition.

Later, it was gradually acknowledged that it was not only the lyrics but also the music which bore the idea of protest. Subsequently, it was increasingly felt that the music in a protest song isn’t strictly subordinated to the lyrics. This view was proposed by Ron Eyreman and Andrew Jamison in Music and Social Movements: Mobilizing Traditions in the Twentieth Century. Indeed, one needs only to consider the banning of musical composition of Chopin with elements of the Polish mazurkas in the USSR regime to understand the subversive nature of non-lyrical music.

Furthermore, the place where the protest songs are sung and the manner in which they are sung is another important factor in the effectiveness of the protest songs. Two instances might here serve the purpose of demonstration:

“Irene goodnight, Irene goodnight

Goodnight Irene, goodnight Irene

I’ll see you in my dreams

Sometimes I live in the country

Sometimes I live in town

Sometimes I have a great notion

To jump into the river and drown”

– Goodnight Irene

The abovementioned lyrics of ‘Goodnight Irene’ might as well be passed off as yet another song which deals with sadness. However, the fact that it was written by Lead Belly, a black convict who frequently made commentaries on white political figures, was instrumental in giving it the dimension of a protest song against racial discrimination.

As the essay will attempt to argue, the category of protest songs is a much broader field which does not and should not be allowed to run into straightjackets. So far, the definition of protest songs has been centred on the idea of expression. The expression of one’s dissent through lyrics, through music, through spatial and strategically timed use of protest songs. This essay argues that the notion of protest song lies not only in its expression but also in its reception, or rather, its impression, not only in the implication but also in its inference. One of the most important reasons why impression and inference should form the parameters while defining protest songs is because the most potent life-force of protest songs lies not only in its reception and re-production but also in its dissemination which depends on the quality of referentiality. This leads us to part two of this paper.

PART II | The Power of Reference in Protest Songs

One of the most effective elements of protest songs is their power of generating a chain of references which infuse an otherwise innocuous song with the spirit of protest. As mentioned earlier, the power of operating over references helps the protest songs not only in their overwhelming reception but also in their proliferation and dissemination. This is especially true of those used in protest movements and protest marches. A protest march is a spectacle, but more importantly, a participatory spectacle. Due to its references, protest songs carry a very important function in such a context- that of fostering unity and solidarity among protesters. When one person sings a song, which is sung by strangers all around him/her, one feels that each member in such a situation is connected to every other participant in the group, that they are a part of something larger than themselves. No wonder Martin Luther King Junior has commented upon the value of protest songs in the American Civil Right Movements thus :

“ They (protest songs) invigorate these movement in the most significant way…

These freedom songs give unity to the movement”

– Martin Luther King Jr.

Protest songs function within a system of reference which may be a historical one- of the tradition of protest songs which have existed in the past or conversely, it may also be social, political and cultural reference of the present. The intricacies of these references is sometimes so personal that only a particular social, cultural, political and economic category is able to understand and appreciate it – a very useful trait in politically charged climate of oppression and suppression, which is also often the reason why protest songs are composed in the first place.

The Underground Railroad migration of the African Slaves to the free states and Canada in the late 1700s had been hugely successful, thanks to the reference system of their songs which allowed them to pass the message about escape routes without being detected thus resulting in the freedom of about 100000 slaves.

Michelle Paterson in her brilliant work “Protest Songs : How humans use language and literature to connect, express and explore universal human issues” goes on to explain how a rich system of cultural references in the songs composed by the blacks was pivotal in leading numerous slaves to freedom. Though the African slaves were prohibited from singing their native songs while working in the plantations, they were actively encouraged to learn Christian songs. Some of them even started composing “Christian’ songs in which was encoded the messages and directions about the Underground Railroad. The African labourers had brought along with them the tradition of response-call singing in which a slave working in the plantations would hum a song which would be responded by another slave. By using songs like “Wade in the Water” and “Follow the Gourd”, they were able to employ this system of references and meanings to set themselves free. An example of its function is provided below.

Follow the drinking gourd

Follow the drinking gourd

For the old man is a waiting

For to carry you to freedom

Follow the drinking gourd

The riverbank will make a mighty good road

The dead trees show you the way

Left foot, peg foot traveling on

Following the drinking gourd

– Follow The Drinking Gourd

Follow the Drinking Gourd was one of the most used songs of this period and the references in the song was missed by the White slaveowners as it made use of very specific African cultural references. The hollow body of the gourd vegetable was often used as a water dipper in many parts of Africa. Hence, ‘Gourd’ was equivalent to “Dipper” in the African context and therefore by singing “Follow the drinking gourd”, they were referring to the Big Dipper constellation which points at the North Star and the guide to Canada in the north. “Left foot, peg foot travelling on” referred to a conductor of the Underground railroad called Peg leg Joe who had guided numerous salves to freedom. It is the effectiveness of references which makes a protest song all the more potent.

One such contemporary protest song where the effective use of references have been employed is seen in the following lyrics:

Well, I heard all about your travel ban

Just for countries that don’t fit your business plan

But how can you decide who cannot and who can

You’re the president now, not a business man

With four years in front and only three weeks behind you

You’ve somehow already managed to upset China

And if I could offer a kindly reminder

It’s not okay to grab women by the vagina

– A Kindly Reminder, Passenger

One may listen to the song here.

The importance of references in a protest song can be understood in this song “A Kindly Reminder” by the British singer-songwriter Passenger, where the only way to fully appreciate this song is by understanding the references to the events in the life of ex-president of the US, Donald Trump. Furthermore, the timing of its release, almost immediately after the travel ban imposed by the Trump Administration was what made the song all the more effective.

The two examples cited above demonstrate the use of references by treating the songs as a complete, inert entity. However, as with any work of art, every new protest song effects a change in the relationship in which one song stands to another. Because there has been a long tradition of protest songs, one often notices a tendency in many songs of protest to evoke components of the past. The historical tradition of past struggles bequeaths upon protest songs the weight of a heritage which lends it a certain legitimacy in voicing out one’s cause. “We shall overcome” therefore, does not simply remain a song which was sung during the Civil Rights Movement but a source of hope to numerous struggles around the world. The song has been translated in numerous languages in varied settings with the same effect of giving hope in times of struggle.

Similarly, the racial inequality highlighted by K’naan in waving flag harks back Bob Marley’s Buffalo Soldier:

So many wars, settlin’ scores,

Bringing us promises, leaving us poor,

I heard them say, love is the way

Love is the answer, that’s what they say

But look how they treat us, make us believers

We fight their battles, then they deceive us

Try to control us, they couldn’t hold us

‘Cause we just move forward like Buffalo soldiers

– Wavin’ Flag, K’naan

A similar use of the tradition of the protest song is seen in the song Yerem Bokhim by the Israeli artist Si Heyman which is written in protest against the wall on the West Bank. The song draws a lot for Pink Floyd’s Another Brick in the Wall and adds a whole set of new meaning by substituting “We don’t need no education, we don’t need no strict control” with “We don’t need no occupation, we don’t need no racist wall.”

Such systems of references therefore convert protest songs into a very diverse category where, on the one hand the dynamism of the cultural references lends a fresh reception of the present and on the other hand, the historical heritage lends the gravity to the emergent protest and locates it within a family with a rich heritage.

Part III | The Need to Preserve Protest Music

Protest songs have often been associated with the marginalized – be it the African American, LGBTQ community or adolescent teens. Perhaps, this is the reason why folk music has been a fertile ground for songs of protest. The Punk and Goth subcultures popular among teens is another genre which has proved to be the conservatory of protest songs. One of the reasons for the effectiveness of protest songs is that they live on even after the cause of the protest itself ceased to exist. Songs like John Lennon’s “Give Peace a Chance” and Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the wind” testify to this fact. However, care must be taken while dealing with protest songs for, as much as they are an expression of discontent from the margins to the centre, the process of appropriation may also take place the other way round. There are instances when the protest songs have been used by the very establishment against which the songs are composed. Furthermore, mass production and popular culture directed by globalization has made this process even more intense.

Victor Jara , the founder of the Chilean New Song movement was critical of the commercialization of protest music by the United States and was actively involved in writing protest songs against the far right of Chile who were backed by a US eager to establish the infamous dictator Pinochet. Jara was finally assassinated after a series of brutal torture where his hands were broken and fingers crushed to mock his love for the guitar. His dead body was ridden with forty bullets and displayed on public view by the dictatorial regime. His scathing indictment against the US commercialization of protest songs has outlived the brutality of his murder and speaks to us to this day. In his own words:

“US imperialism understands very well the magic of communication through music and persists in filling our young people with all sorts of commercial tripe. With professional expertise they have taken certain measures: first the commercialization of the so called protest music, second the creation of ‘idols of protest music who obey the same rules and suffer from the same constraints as the other ‘idols’ of consumer music industry- they last a little while and then disappear. Meanwhile they are useful in neutralizing the innate spirit of rebellion of young people. The term ‘protest song’ is no longer valid because it is ambiguous and has been misused. I prefer the term revolutionary song.”

– Victor Jara

This critique of Jara is important in order to tackle the contemporary commercialization of protest songs. Because this essay considers protest songs as a dynamic category, it is possible, and necessary, to reclaim the lost voices of dissent. In this context, one of the most magnificent protest songs which could have been a potent tool to critique the façade of globalization succumbed to the charms of a globally powerful MNC. Wavin’ Flag by K’naan in its original form was a scathing critique against neo-imperialism and voiced the aspirations of so called “backward nations” and the yawning inequality that exists. Ironically, this global earworm was used by Coca-Cola as a happy sounding song and it is the Coca Cola version which was used to saturate global consciousness. The original version was censored in many countries and till date is not very well known. This protest song was sacrificed in the spectacle of 2010 World Cup in South Africa.

This essay began by describing the nature of protest songs. It ends by describing how a protest song was heavily neutralized by commercially reducing it to a happy jingle. Thus, we can see how vast and dynamic the category of protest song is and how the expression and impression, the implied and the inferred is of equal importance while exploring and defining the nature of protest songs, Furthermore, because protest songs occupy the gap between the margin and the center and because it can be used to the benefit of either, the need to reclaim songs of protest is of a great importance. Owing to the necessity and importance of the process of reclamation, this essay ends with the original lyrics of Wavin’ Flag, for which a video link has been attached below. This is a small attempt to recover and reuse a fragment of an identity which remains threatened by oblivion:

Born to the throne, stronger than Rome

But violent prone, poor people zone,

But it’s my home, all I have known,

Where I got grown, streets we would roam.

But out of the darkness, I came the farthest,

Among the hardest survival.

Learn from these streets, it can be bleak,

Accept no defeat Surrender retreat

So we struggling, fighting to eat and

We wondering when we’ll be free,

So we patiently wait, for that fateful day,

It’s not far away, so for now we say

When I get older, I will be stronger

They’ll call me Freedom

Just like a Wavin’

Flags are waving, flags are waving…

To cite this essay, copy the link below:

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ron Eyreman and Andrew Jamison –Music and Social Movements: Mobilizing Traditions in the Twentieth Century

Michelle Paterson –“Protest Songs : How humans use language and literature to connect, express and explore universal human issues”

Dorian Lynsky , 33 Revolutions in a Minute

Joan Jara –An Unfinished Song

Salamisallah Tillet – The Return of the Protest Song

Steve Layafette – The legacy of protest music.

Margaret Smith – Singing along the rails- Songs during the Industrial Revolution