Hunger, a 2008 historical drama film based on the 1981 Irish Hunger Strike focuses on the hunger strikes by the Republican prisoners in Northern Ireland in response to the withdrawal of Special Category Status. Directed by Steve McQueen, it follows the story of Bobby Sands, who started the strike and died during it. Through his and other cellmates’ journeys, the themes of violence, resilience and morality are promptly reflected. The absence of dialogues and music makes the film’s title even more heard, almost like a shriek and then a deafening silence. Not only does it suggest hunger, but also the lack of social and human interaction, a healthy sanitary environment, and a sense of time and purpose.

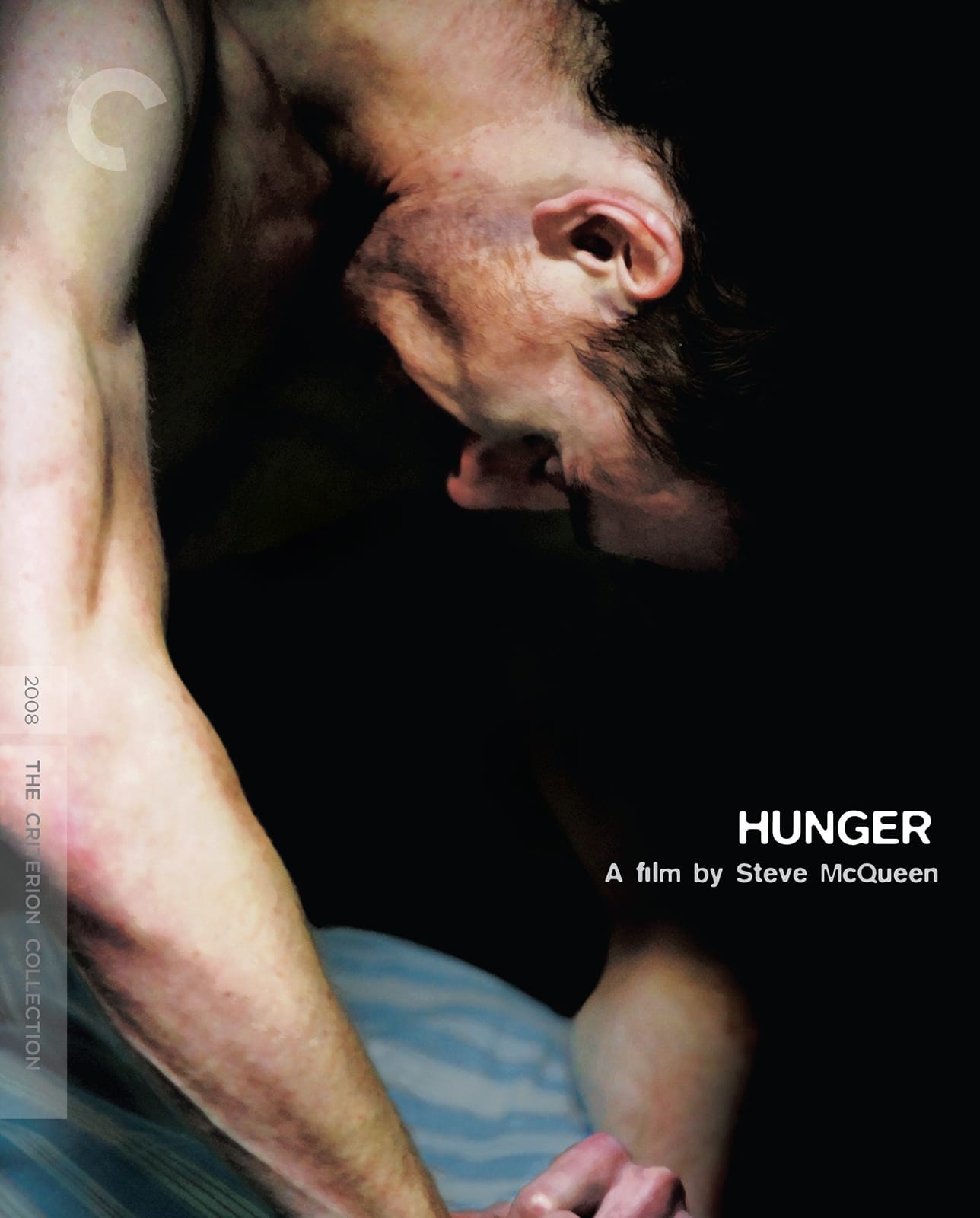

HUNGER (2008)

Director: Steve McQueen

Producer: Laura Hastings-Smith, Robin Gutch

Cast: Michael Fassbender, Liam Cunnningham

Release Date: 31 October 2008

Budget: £1.7 million or 2.08 million USD

The trailer of the film opens with an eerie strum of an instrument, as the scenes start unfolding one by one with Margaret Thatcher’s 1981 speech in Belfast dawns in. The scenes that follow are chilling to the spine, from violence by the state to the resilience of the prisoners who demand nothing but political status along with some other fundamental rights in the prison. While their agony is hidden in the background sounds are constantly present during the length of the trailer, and insight into the prison guards and the army is provided, which proves how inhumane the conditions are. McQueen believes that the film’s importance is determined by its impact, and narrates how he has had a first-hand experience of the strike, the impact of which was felt in the whole country and made people afraid to talk about it, lest they also be imprisoned for the crime of sedition.

Watch the trailer here: HUNGER Trailer (2008) – The Criterion Collection

The film opens with a bunch of people banging their utensils on the table, so hard that it feels pounding and alive and it comes to a still, to open at a scene at prison guard Raymond Lohan’s house, where he prepares to leave for work asynchronous sound of water flowing through the tap is intentional to establish the aloofness of the scene as well as the character. He goes through his normal morning routine, tends to his wounds, gets ready for work, eats breakfast, and checks for bombs under his car. He is the aloof, distrusting guy who does not mingle with his comrades and goes about his day alone. The lack of real conversations up until now maintains the eeriness around his personality but there seems to be a jump in between the scenes as he now tends to his open and gashed wounds and smokes his cigarette alone while staring into the oblivion with a large patch of sweat in the back of his uniform. A part of Margaret Thatcher’s Belfast speech is played, “There is no such thing as political murder, political bombing or political violence. There is only criminal murder, criminal bombing and criminal violence. We will not compromise on this. There will be no political status.” The playwright has consciously used this as the first real dialogue in the film if the lewd locker room talk of the prison guards is to be ignored. This statement gives an insight into the current situation, the protection, ongoing resistance and presence at the start of this resistance, Maze Prison.

One of the new political IRA inmates is brought in the next scene. There is no exchange of dialogue between the prisoner and the prison guards, only the prisoner’s confirmation of being a non-conforming prisoner is important as the guards don’t even bother writing his name down on their register. With no prompt of being talked to, Davey Gillen states that he will not wear the prison uniform and starts stripping. The familiarity on how to deal with the police and guards is sickening because this shows the resistance had been going on for a while, so heard that even a new prisoner knows what his next words and actions should be. He is handed a blanket and is walked through a silent hallway, a gash on the wound is also seen on top of his head, left untreated and bleeding. In his cell, he meets Gerry, another of the non-conforming prisoner who has smeared his excrement on all four walls as a part of his dirty protest. In the dark, dingy and smelly cell, infested with maggots, they both sit down and make small talk, about knowing one of the other IRA comrades who lived near Gillen’s place. The scene of the hunger strike follows next, as their cellmates throw away the food that is provided to them and make an opening under the prison door to urinate outside of their cells. The blanket and dirty protests were key to the 1981 strike as their grants were not conferred by the Prime Minister. Withdrawal of Special Category Status, which protected their certain rights as political prisoners and granted them a better life than the ordinary criminals in the jail led to blanket protest, where the prisoners refused to wear the regular prison uniform and chose to either roam around naked or fashion their blankets as their garments. However, in due time, to resist their resistance, the prison guards themselves started to beat up the prisoners when they were out of their cells alone, doing chores. After refusal from the prison officials to provide them with their own lavatory and showers in their cells to escape the attack of the prison guards, they refused to leave their cells for anything, not even to empty their chamber pots and started to smear their excrement on the walls of the cells. The IRA prisoners who were a part of this dirty protest talked about their experience in the prison during their fight for special status, saying :

“There were times when you would vomit. There were times when you were so run down that you would lie for days and not do anything with the maggots crawling all over you. The rain would be coming in the window and you would be lying there with the maggots all over the place.”

The prison officers try to break through the prisoners’ “no wash protest” by violently and forcibly dragging them out of their cells, where they were given a haircut forcibly and a forced bath too. On one such occasion, a prisoner named Bobby Sands is forced out of his cell to break through his protest but when he spits on Prison Officer, Lohan punches him in the face and when going for a second punch, he hits the cemented wall as Sands ducks down to dodge the punch. His knuckles are wounded and gashed but he still forcibly cuts his hair and overgrown beard and then prompts the guards to throw him in the tub full of water to wash him, where he pokes him with the cleaning mop several times too. This brings us back to the scene where Lohan is washing his wound, going out for a smoke with a large sweat patch on the front and back of his uniform. Bobby Sands, on the other hand, is carried out of the tub half unconscious. While the prisoners are out, the rubber-suited officers from head to toe try to clean their cells using a high-power spray hose. On his monthly visit from his parents, Bobby wears second-hand civilian clothes and meets his parents, assuring them the prison authorities are taking care of his food as well as wounds and asks them to not worry and instead take care of themselves.

People try to sneak in things for their friends and family in the prison, from pieces of paper to a radio. Sands gets several chits and pieces of papers asking to negotiate, after a meeting with the priest, which he promptly burns with the cigarettes made out of the Holy Bible. The next day, the prisoners are escorted out of their cells and provided with second-hand civilian clothes yet again while the guards stand on the opposite side of the wall, sniggering at them. The confusion on Bobby’s face is apparent, as he might be wondering if this was really an extension of an olive branch from the officers but this soon settles down as he is sitting in his well-furnished cell, contemplating what to do with his clothes. A shot of the rest of the prisoners waiting for their orders is so seen, as Bobby keeps tapping his foot incessantly on the floor, faster as the second passes, the scenes getting shorter too, up until Bobby starts thrashing the furniture around, breaking it and tearing the clothes apart. The jump cuts from the shots to introduce new characters who are all following through the same action Bobby does, casing mayhem in there. McQueen, the director of the film, rather than showing us each cell being trashed, lets us hear the ruckus from outside the cells, as the spectators, or the prison officers. He has heavily depended on such background noises throughout the film to draw more attention to this movement of resilience. Another long shot of the guard taking the prisoners’ name cards out of their cell plates follows, with an eerie silence before the impending storm. The officers, in full riot gear, assault the prisoners and force them for mouth and rectum probing using the same set of gloves for everyone.

While the prisoners are tormented like this inside the prisons, IRA officers take to killing the prison officers and guards outside of the prison to strengthen their movement. Lohan is killed when he is on a visit to his mother in an old age home, where he dies with his head on her lap while the mother stays unmoved, unclear if she cannot talk or chooses not to. Sands, in prison, is visited by Father Dominic, the priest who is asked to shoulder the responsibility of making Sands realise the moral obligations of his actions and their consequences. This shot, a little over 17 minutes is the most important one, shot in a dark room, with only light seeping in from the railings above, as if this was an intervention by the gods, with the priest and the ‘sinner’ present. This scene was shot four times, during one of which, the boom operator had collapsed, and the director resorted to using the fourth and the final cut. The display of medium shots to introduce the characters and the shoulder shot while they’re justifying their actions, and telling their sides of the story is what makes his scene so impeccable that it is studied by critics all across.

The narration of an incident from Sands’ childhood, the foul and his act of killing it to lessen its sufferings, all make father Dom realise the plight of the situation, as an over-the-shoulder shot settles on his face, a little agonized. He realises that Sands refuses to stand there and do nothing, despite putting his life in danger. A long shot of a guard wiping off the urine from the corridor follows, with a part of the Belfast speech of Margaret Thatcher still in the background, and stays until the job is done. An out-of-focus shot is on the screen as Sands lies down in a prison hospital, still on his hunger strike. He is extremely weak and is deteriorating quickly. A doctor briefs about the situation to Sand’s parents about his health. The horrifying details are saved by hiding the deteriorating body of Sands behind the doctor who is dressing the wounds, to save the audience some horror. His doctor in charge is kind and caring; however, the second shift doctor supports the views of a loyalist paramilitary group, UDA, and is as callous and lacks empathy, against whom Bobby does stand in defiance, even if for a fleeting second. A visit from his past self, a sign of his innocence and youth, he follows his days of cross country, as the scene finally cuts with his death, with a bunch of birds flying off from the tree as if symbolising the release of the life. The film ends with his final words to father Dom, “There’s no need, Dom.”